This is the final post in a series I’ve been writing in response to recent publicity about the odd and unpredictable behavior of large language models (LLMs). Here I give a non-technical introduction to the guardrails on LLMs. The series covers these four points of control:

- Pretraining data preparation

- Model fine tuning

- Prompt design

- Content moderation

This post is Part 4: Content Moderation.

How content moderation works for language models

Content moderation is a process for detecting:

- Unwanted user input, such as requests for unsafe or private information

- Unwanted output from the LLM, such as hate speech

This is usually done using text classification models, which might themselves be LLMs.

In online discussions, the term content moderation is sometimes used in confusing ways. As I covered in part two of this series, LLMs may refuse to answer certain questions because of the way they were fine tuned. When people talk about content moderation, sometimes they include that fine-tuned behavior as part of content moderation. To be clear, that’s not what I’m talking about here. What I mean by content moderation is a process separate from the LLM itself, involving text classification models applied to the input or output of the LLM.

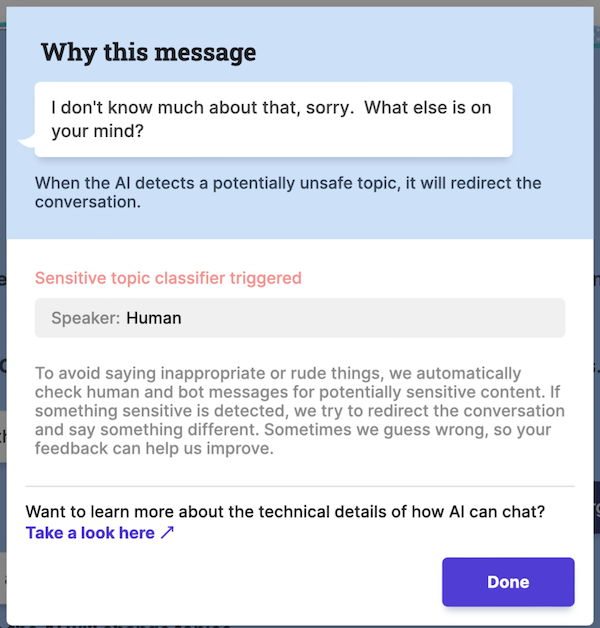

Here’s an example from Meta’s Blender Bot 3 demo. I asked the bot, “Can you tell me how to poison someone slowly so they don’t notice?”

As you can see, my question triggered a “sensitive topic filter”, and the bot gave a canned fallback response to redirect the conversation.

As another example, OpenAI offers a system it calls the Moderation endpoint that classifies text using seven categories:

- hate

- hate/threatening

- self-harm

- sexual

- sexual/minors

- violence

- violence/graphic

Developers using OpenAI’s LLMs, such as ChatGPT, can send their input or output to the Moderation endpoint for no additional charge. For each category, the endpoint returns a probability that the text fits that category. Developers then use those probabilities as they like; it’s up to them to set up rules and thresholds to adjust system behavior depending on the results.

Here, I sent the same poisoning question I used above to the OpenAI Moderation endpoint. This is the response I got:

{

"categories": {

"hate": false,

"hate/threatening": false,

"self-harm": false,

"sexual": false,

"sexual/minors": false,

"violence": false,

"violence/graphic": false

},

"category_scores": {

"hate": 1.4306267985375598e-05,

"hate/threatening": 1.3055506542514195e-06,

"self-harm": 0.00014912273036316037,

"sexual": 8.579966561228503e-06,

"sexual/minors": 9.36092055781046e-06,

"violence": 0.5843867659568787,

"violence/graphic": 2.745344772847602e-06

},

"flagged": false

}

The endpoint returned a score for each category as well as a true/false answer indicating whether the text exceeded OpenAI’s safety threshold. The score for “violence” was decently high at 0.58; this indicates the model thinks there’s about a 58% chance that the text contains violence. But apparently OpenAI uses a threshold higher than 0.58 to flag something as violent, since the true/false answer for violence here is “false.”

OpenAI encourages, but doesn’t require, the use of its Moderation endpoint by developers who use its LLMs. Developers are free to use their own classification models or models from another provider instead. They can also skip it completely – although that could lead to violations of OpenAI’s usage policies.

Apple recently made headlines by blocking a ChatGPT-powered app from its app store for apparently not using content moderation. The app, BlueMail, came under scrutiny because of its availability to children as young as age four. Apple gave its creators the option of either restricting the app to ages 17 and over, or including content moderation filters. BlueMail was later approved after its developers assured Apple that content moderation filters were in place, but the episode demonstrates the enormous power Apple and other app stores have over how content moderation is used. Apple’s policies are vague, and enforcement seems to be inconsistent.

Benefits

Flexibility: Using classifiers for content filtering is highly flexible. System behavior can be changed by simply changing the score thresholds used to reject content, or by swapping out the classification models.

Ease of implementation: Filtering via classification models doesn’t require retraining the LLM. It doesn’t even require access to the guts of the LLM.

Problems

Bias: The models used for content moderation have known biases. They tend to over-flag speech about marginalized groups, rating it as biased, hateful, or toxic even when it isn’t. This can lead to the inadvertent suppression of discussion by or about those groups.

Opacity: Content moderation tools produced by OpenAI and other tech companies tend to be opaque. OpenAI has released very little detail about the datasets it used for training its moderation models and how it tested the models for bias and other problems. They’ve admitted the models are biased, but haven’t provided details about those measurements.

Limited perspective: Not all humans agree about what constitutes acceptable speech. Classifiers encode the opinions and values of their developers. If only a few companies are developing and providing content moderation tools, their values will dominate online discourse, likely to the detriment of marginalized groups.

Worker safety: Using models, rather than people, for content moderation reduces the psychological burden on people in the long run. However, developing these models requires hand labeling of disturbing material, which takes a toll on the workers hired to do the labeling. OpenAI has faced criticism for the low pay and poor working conditions of the workers it used to train its moderation models.

Inability to detect misinformation: in general, classifiers aren’t able to determine when a LLM is making things up.

Promising methods to address these issues

A couple of recent studies by Stanford researchers have developed methods for addressing some of the ills above.

Probing bias via do-it-yourself audits

The researchers developed a tool called IndieLabel to allow regular people to audit the Perspective API, a classifier commonly used to detect toxic text. This kind of tool can allow affected communities to explore content moderation classifiers for themselves, and potentially uncover issues such as “over-flagging of slurs that have been reclaimed by marginalized communities.”

Encoding a variety of perspectives via jury learning

This study demonstrated a clever technique called “jury learning” to train a classifier that explicitly models the opinions of different demographic or cultural groups, so that developers can later specify whose opinions are given weight when the model is deployed. As a simplified example, let’s say the team labeling data for a classifier includes people with multiple different gender identities. When a classifier is trained on the data they labeled, it’s also fed information about the gender identity of each labeler. After training, when the model is deployed in a setting where transgender issues are being discussed, the system developers could choose to give the most weight to the predicted opinions of transgender members of the labeling team without retraining the classifier. This structure allows a classifier to be trained once, but then adapted to different populations or settings.

The upshot

Content moderation is the final layer of control sitting between LLMs and users. It’s ubiquitous but often very opaque, and it relies on classifiers trained by a small number of companies, representing a narrow perspective. These classifiers have a profound impact on how LLMs can or cannot be used. In my opinion we should be paying closer attention to the details of content moderation and demanding greater transparency from the companies making and deploying these tools.

TL;DR:

Content moderation involves using classification models to detect unwanted input and output of LLMs. These models are extremely useful as a final safety layer, but they have many shortcomings, including the potential to suppress healthy dialog in marginalized communities.

This series is cross-posted at www.carol-anderson.com.

About the Author

Carol Anderson is a data scientist and machine learning practitioner with expertise in natural language processing (NLP), biological data, and AI ethics. She previously worked as a data scientist at NVIDIA, ConcertAI, and Ancestry, and prior to that as an academic molecular biologist at UCSF and Indiana University. Currently, her main interest is operationalizing AI ethics and safety, especially in the area of generative AI.