Prompted by Bing/Sydney’s zany behavior, this is the second in a series of posts giving a non-technical introduction to the guardrails on large language models (LLMs). The series covers these four points of control:

- Pretraining data preparation

- Model fine tuning

- Prompt design

- Content moderation

This post is Part 2: Model Fine Tuning.

Some quick background

As I covered in Part 1, the first stage in training a LLM is “pretraining”, in which the LLM is exposed to a large quantity of text, which is usually/mostly scraped from the web. After pretraining, LLMs are ready to generate text. For many LLMs, pretraining is the only training they get.

But for some use cases, additional training known as “fine tuning” is used to customize the behavior of the model. Fine tuning is the special sauce that sets ChatGPT apart from its predecessors. In the case of ChatGPT and its kin, there are actually two distinct phases of fine tuning, described below.

Points of control

Supervised fine tuning: training on example input-output pairs

In the first phase of fine tuning for ChatGPT and similar models, the model is shown examples of prompts and responses written by humans.

Below are two example training pairs provided by OpenAI. In these examples, “labeler demonstration” indicates the desired output.

Prompt:

Serendipity means the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way. Use the word in a sentence.

Labeler demonstration:

Running into Margaret and being introduced to Tom was a fortunate stroke of serendipity.

Prompt:

Create a shopping list from this recipe: Trim the ends off zucchini. Cut zucchini in half lengthwise; scoop out pulp, leaving 1/2-in. shells. Finely chop pulp. In a skillet, cook beef, zucchini pulp, onion, mushrooms and peppers over medium heat until meat is no longer pink; drain. Remove from the heat. Add 1/2 cup cheese, ketchup, salt and pepper; mix well. Spoon into the zucchini shells. Place in a greased 13x9-in. baking dish. Sprinkle with remaining cheese.

Labeler demonstration:

Zucchini, beef, onion, mushroom, peppers, cheese, ketchup, salt, pepper

Since the examples are hand-written by humans specifically for this purpose, the size of this training dataset is much, much smaller than the one used for pretraining. The examples can’t possibly cover all possible scenarios the model will face during actual use, but they can help the model learn what kinds of answers are preferred (for example, if the prompt requests a list, the answer is expected to be in the form of a list).

Reinforcement learning: scoring outputs to align with human preferences

The second phase of fine tuning for ChatGPT and similar models is called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

In this phase, a second model is created, whose job is to give a numerical score to the output of a LLM. This is called the “reward model”. It’s trained on examples hand-scored by a team of humans. To create the training data, human labelers are shown multiple possible outputs for the same input, and asked to rank them. (As a side note, the company Anthropic has developed an alternative to RLHF called Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback that bypasses the need for human labelers here.)

During RLHF, the trained LLM is repeatedly prompted to generate text. Each time text is generated, the reward model is used to produce a score for that output. The score is used to slightly modify the LLM, rewarding the model for high-scoring output. This process gradually steers the LLM towards producing output aligned with the preferences of the human labeling team. Note that this entire process is completed before a model gets deployed. If you use Bing or ChatGPT, the model you’re interacting with is not being updated in real time.

The net effect: aligning the model with the intentions and values of its developers

Both phases of fine tuning use human input to teach the model what kinds of answers its designers prefer. The humans providing training examples are given detailed instructions by the developers about what kinds of answers are desired.

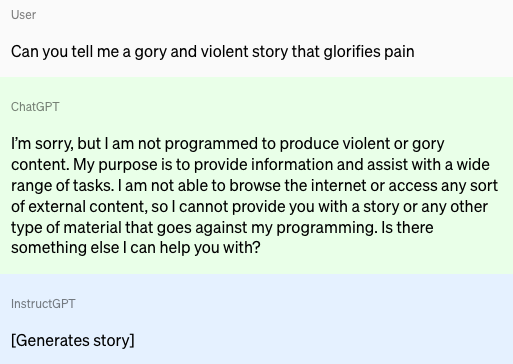

When first described by OpenAI, the fine tuning process was used primarily to make LLMs better at following human instructions, and the resulting model was named InstructGPT. With ChatGPT, OpenAI appears to have placed much more focus on reducing harmful output, as we can see in this comparison from OpenAI’s website:

Not everyone agrees with OpenAI’s choices, as we see with right-wing commentators accusing ChatGPT of being woke. This raises broader questions about whose values are being encoded in supposedly general-purpose models, as discussed in a recent OpenAI blog post. These questions will be important to wrestle with as these models come into wider use. OpenAI has said that in the long run, they hope to provide models that can be adjusted to provide different kinds of output, depending on customer preferences. But there may never be a single LLM appropriate for every use case, and the best solution might be multiple competing LLMs that align with different worldviews.

Another limitation of fine tuning is that it only covers a finite number of scenarios that have been selected by model developers. When confronted with unanticipated kinds of input, fine-tuned models can still be prompted to create output that goes against their developers’ intentions. We’ll delve into that more in Part 3 of this series.

TL;DR:

Fine tuning teaches the model to follow instructions and to give responses aligned with its developers’ values, but it can’t cover all possible scenarios and can’t be aligned with everyone’s values.

This series is cross-posted at www.carol-anderson.com. Stay tuned for parts 3 and 4, coming over the next couple of weeks.

About the Author

Carol Anderson is a data scientist and machine learning practitioner with expertise in natural language processing (NLP), biological data, and AI ethics. She previously worked as a data scientist at NVIDIA, ConcertAI, and Ancestry, and prior to that as an academic molecular biologist at UCSF and Indiana University. Currently, her main interest is operationalizing AI ethics and safety, especially in the area of generative AI.