Large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT are trained on massive datasets of web-scraped data. Research shows that they memorize some of it, and can regurgitate it verbatim – including personal data and copyrighted material.

Is that a problem?

One common point of view is that it isn’t a major problem, because the memorized material is (typically) already available on the public web. Since it’s already out in public, who cares if a language model happens to spit it out too? Here, I’ll argue that we definitely should care, because LLMs pose unique privacy and intellectual property risks.

What are the risks?

Violating the right to be forgotten

In Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models (Carlini et al., 2021) the authors show that personal data, such as addresses and phone numbers, can easily be extracted from GPT-2 without any prior knowledge of the information. (As a side note, their attack method requires access to the probabilities produced by the model; I’ll return to this later in the “Solutions” section).

The personal data GPT-2 memorized was on the public web at some point in time. But some of it may have been posted without the knowledge or consent of the people concerned. Moreover, data subjects in some jurisdictions, including the EU, have the “right to be forgotten”, i.e. to have their data deleted or destroyed upon request. LLMs can end up serving as a long-term repository for personal data even after it’s been removed from the public web, impinging on the right to be forgotten.

Emitting info in an unexpected context

Even when a LLM is trained only on public information, privacy violations occur if a LLM produces that information in an unrelated context. Carlini et al. point this out:

“…data memorization is a privacy infringement if it causes data to be used outside of its intended context.”

They refer to this as “contextual integrity violation.” As an example, someone’s contact information might be associated with open-source code they’ve developed, but then inappropriately emitted in a chat on an unrelated topic. A contextual integrity violation also occurs when a LLM incorrectly combines information from two sources:

“In one example, GPT-2 generates a news article about the (real) murder of a woman in 2013, but then attributes the murder to one of the victims of a nightclub shooting in Orlando in 2016. Another sample starts with the memorized Instagram biography of a pornography producer, but then goes on to incorrectly describe an American fashion model as a pornography actress.” (Carlini et al., 2021)

Copyright and license infringement

GitHub Copilot is a code-writing assistant based on OpenAI’s Codex model, which was trained on public source code. Sometimes it spits out blocks of code verbatim from its training corpus.

One of the key problems with this is code licensing. Some of the code in the training set carries licenses that require author attribution and/or the preservation of rights in derivative works. Yet when Copilot regurgitates code, it usually doesn’t regurgitate the license along with it. (The licenses are often found in a separate file, and no effort was made to link code with its license during training set creation, as far as I know.)

In one highly publicized example, a user recorded a video of Copilot generating a large block of copied code, and then suggesting the wrong license to go along with it:

I don't want to say anything but that's not the right license Mr Copilot. pic.twitter.com/hs8JRVQ7xJ

— Armin Ronacher (@mitsuhiko) July 2, 2021

Copilot is currently the defendant in a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of GitHub users, alleging violations of GitHub’s own terms of service and privacy policies, and of various laws governing copyright and privacy.

Exposure of non-public data

LLMs are sometimes trained on private datasets. One example is the chatbot Lee-Luda, trained by South Korean company 스캐터랩 (Scatterlab) and deployed through Facebook Messenger. Lee-Luda was trained on billions of private chats, and soon began revealing personal data obtained from the chats, such as names, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses, even though ScatterLab claimed to have removed personal data prior to training.

Solutions

There’s no comprehensive solution to the problems above. But some approaches can help mitigate the risk:

Deduplicating training data

Memorization of text is much more likely when that text appears multiple times in the training corpus (Carlini et al., 2021). Deduplicating training data helps to mitigate this risk. As an additional benefit, deduplicating also improves language model performance (Lee et al., 2022). But deduplication doesn’t completely eliminate memorization (Kandpal et al., 2022). There is clear evidence that LLMs can memorize text that only appears once in the training data (Perez et al., 2022).

Cleaning or curating training data

Attempts should be made to remove personal information from training data. But this is a lot harder than it sounds, as What does it mean for a language model to preserve privacy? (Brown et al., 2022) points out:

“…private information is context dependent, not identifiable, and not discrete.”

The authors give a fictional example of a chat between Alice, Bob, and Charlie about Alice’s divorce and custody battle. All the messages have the potential to reveal private information about Alice, but it might be very difficult to automatically detect Bob and Charlie’s messages as containing sensitive information. Rather than trying to sanitize existing data sets, the authors suggest training language models on datasets specifically intended for public use.

API hardening

Putting models behind an API that only allows access to the generated text, and not the underlying probabilities produced by the model, can help mitigate privacy risks. As noted above, the attack carried out by Carlini et al. to find memorized data required access to the model’s probabilities. Again, while API hardening is an important step, it’s an incomplete solution. Targeted attacks and unprovoked privacy violations can still occur.

Differentially private training

Training with differential privacy (DP) methods has the potential to offer privacy guarantees; but applying this to text is a lot trickier than it initially sounds. DP is typically described as a guarantee that you cannot determine whether any individual’s data was included in a dataset by looking at the model’s output. More formally, DP actually guarantees that you can’t tell whether a particular record was included in the dataset. The tricky part here, as discussed by Brown et al., is defining what a “record” is when it comes to training language models. Secrets can be distributed across multiple documents and multiple users. As the authors put it, “withholding any specific unit of data from the dataset cannot guarantee protection of privacy.”

Leakage testing and analysis

Developing methods to test models for data memorization and leakage is an active area of research (for example, Inan et al., 2021; Perez et al., 2022). These methods can be used to compare leakage between different types of models trained on the same data, to guide removal of problematic material from training data, and to inform input and output filters.

Filtering input and output

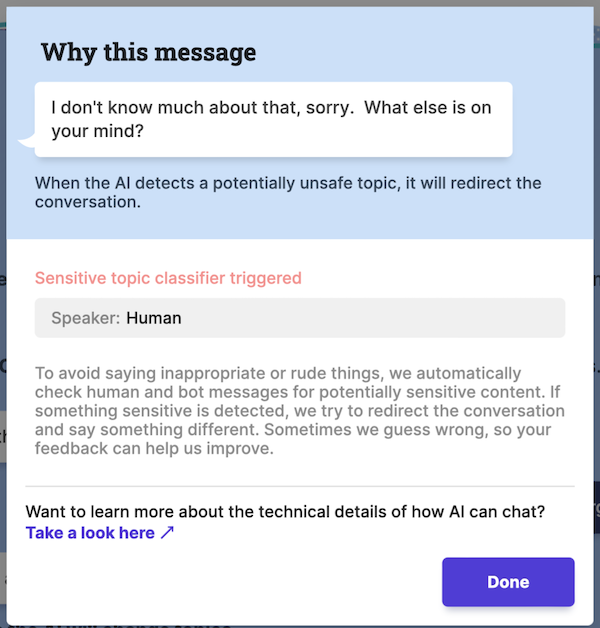

Many language-model-based products incorporate filters to weed out inappropriate requests before they reach the model. The example below shows how Meta’s BlenderBot 3 reacted when I asked for Mark Zuckerberg’s home address:

Filtering the output is another useful approach; for example, Jasper.ai suggests feeding the output of their AI writing assistant to a plagiarism detector.

All of the above solutions have pitfalls; none offer complete guarantees of privacy and copyright protection. And a critical legal question remains unresolved: what responsibility do model providers have to ensure their products don’t violate privacy and intellectual property rights? This will undoubtedly be an active area of discussion and litigation in the coming years.

References

Brown, H., Lee, K., Mireshghallah, F., Shokri, R., & Tramèr, F. (2022). What Does it Mean for a Language Model to Preserve Privacy? 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2280–2292. link

Carlini, N., Tramèr, F., Wallace, E., Jagielski, M., Herbert-Voss, A., Lee, K., Roberts, A., Brown, T., Song, D., Erlingsson, Ú., Oprea, A., & Raffel, C. (2021). Extracting training data from large language models. 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), 2633–2650. link

Inan, H. A., Ramadan, O., Wutschitz, L., Jones, D., Rühle, V., Withers, J., & Sim, R. (2021). Training Data Leakage Analysis in Language Models. In arXiv [cs.CR]. arXiv. link

Kandpal, N., Wallace, E., & Raffel, C. (2022). Deduplicating Training Data Mitigates Privacy Risks in Language Models. In arXiv [cs.CR]. arXiv. link

Lee, K., Ippolito, D., Nystrom, A., Zhang, C., Eck, D., Callison-Burch, C., & Carlini, N. (2022). Deduplicating Training Data Makes Language Models Better. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 8424–8445. link

Perez, E., Huang, S., Song, F., Cai, T., Ring, R., Aslanides, J., Glaese, A., McAleese, N., & Irving, G. (2022). Red Teaming Language Models with Language Models. In arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. link

An earlier version of this post was published at www.carol-anderson.com.

About the Author

Carol Anderson is a data scientist and machine learning practitioner with expertise in natural language processing (NLP), biological data, and AI ethics. She previously worked as a data scientist at NVIDIA, ConcertAI, and Ancestry, and prior to that as an academic molecular biologist at UCSF and Indiana University. Currently, her main interest is operationalizing AI ethics and safety, especially in the area of generative AI.